Was G.K. Chesterton a Theologian?

Stratford Caldecott

G.K. Chesterton was not a “theologian” if by that you mean a professional theologian. On the other hand, very few have applied thought to religion as effectively as he. Chesterton once described theology as a “sublime detective story” in which the purpose is not to discover how someone died, but why he is alive. The notable author may qualify as a theologian after all.

He was not a theologian in the sense of having a degree in theology. He was not a theologian in the sense that he wrote books of theology — exploring, for example, the advantages and disadvantages of applying the title “Coredemptrix” to the Blessed Virgin Mary or possible solutions to the Filioque controversy with reference to the Christology of the Cappadocian Fathers. He was not a theologian in the sense that he identified himself as such or what he wrote as theology. For example, he writes that “supernatural truths are connected with the mystery of grace and are a matter for theologians; admittedly a rather delicate and difficult matter even for them”.

On the other hand, we should note Chesterton’s comment in The New Jerusalem: “Theology is only thought applied to religion”. Very few have applied thought to religion as effectively as he. On another occasion, Chesterton described theology as a “sublime detective story” in which the purpose is not to discover how someone died, but why he is alive. The notable author of the “Father Brown” stories and President of the Detection Club may qualify as a theologian after all.

Theology in East and West

The Eastern Orthodox Church only honours three people in the whole history of the Church with the formal title “Theologian”: the author of the Fourth Gospel, Gregory Nazianzen (330-390) and Symeon the New Theologian (949-1022). Each was a “mystic” (in Lossky’s sense): that is, he spoke or wrote from an experience of union with God. The true theologian is caught up in the life of God; theology or “theo-logic”, the logic of God, is something higher than human reason: “For my thoughts are not your thoughts: nor your ways my ways, says the Lord” (Is. 55:8-9).

The great example, of course, of a mystery that human thinking could not have discovered on its own, and which is known only by faith, is the Trinity: the fact that God is One undivided nature, yet Three Persons. For a human being to theologize is to attain “things beyond the mind of man” (1 Cor. 2:10), and that is possible only by the grace of participation in God. In the case of the three Theologians we find it impossible to separate their “thought” from their “spirituality”. This is the whole point of the Eastern and ancient spirituality of Christianity, as it was recorded in that collection of texts called the Philokalia: thought must be integrated with spirituality, and the mind with the heart.

The Latin Church, of course, was more or less united with the Orthodox throughout the first millennium. The “New Theologian” died in 1022; the great Schism took place in 1054. But right up to modern times Western theology has been understood as a prayerful unfolding of what Scripture can reveal to the eyes of faith.

How it was that in many modern universities, and even in some cases modern Catholic universities, theology became the name of a mere academic subject like biology or history or maths is a long story. No longer “queen” of the sciences, theology tends to be viewed as their poor relation: a type of embarrassing, incontinent great grandmother the sciences might prefer to keep hidden upstairs when visitors come to tea. Fortunately theology is not confined to the modern university — and even there we may find theologians who regard prayer as the indispensable foundation of their subject. They are encouraged and supported by the magisterium of the Church.

The 1990 document of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith on The Ecclesial Vocation of the Theologian, speaks of the relationship of love and method in theology: “Obedient to the impulse of truth which seeks to be communicated, theology also arises from love and love’s dynamism” (section 7). Thus we may say that even today both East and West are agreed on this fundamental point, that, just as the primary theology in the Church is Scripture itself, and the primary theologians are the Evangelists (especially John), so all secondary theology derives from Scripture, the study of which the Second Vatican Council describes as the very “soul” of theology (Dei Verbum, 24).

Theology and the Convert

After these preliminaries, we must turn to the question of G.K. Chesterton and his relationship to “theology” thus understood. I will call to the witness box the Western theologian who has done more than any other in our time to reintegrate the study of Scripture and the study of theology with the life of faith: Hans Urs von Balthasar, the Swiss theologian who died in 1988.

Balthasar’s theological career can be said to have begun when he realized during his Jesuit training how utterly boring theology was. He ended up sitting through his lectures with plugs in his ears, reading the complete works of St Augustine under the desk. As he says, “My entire period of study in the Society of Jesus was a grim struggle with the dreariness of theology, with what men had made out of the glory of revelation. I could not endure this presentation of the Word of God! I could have lashed out with the fury of a Samson. I felt like tearing down, with Samson’s own strength, the whole temple and burying myself beneath the rubble.”

This righteous indignation in fact fuelled a more constructive project: the rebuilding of modern theology in a great trilogy of series, each containing several massive volumes, on the themes of Beauty, Goodness and Truth. A true theologian, for Balthasar, is one who perceives and helps to reveal the glory of God revealed in Christ. He recognized in Chesterton an exponent of what he called the “lay style” of theology (mentioning him indeed in the same breath as Newman), and he finds in Chesterton’s humour the providential response to much of the “bestial seriousness and desperate optimism of modern world views”; a brilliant demonstration that only in Christianity (and ultimately only in Catholicism) “can one preserve the wonder of being, liberty, childlikeness, the adventure, the resilient, energizing paradox of existence”.

A wonderful essay of Chesterton’s in The Common Man called “Reading the Riddle”, begins by describing the success of a trendy theological book called The Great Problem Solved. The success of this book was due to the fact that people were buying it under the impression that it was a detective story; and, of course, they ended up being disappointed. Chesterton then asks, “Why is a work of modern theology less startling, less arresting to the soul, than a work of silly police fiction? Why is a work of modern theology less startling, less arresting to the soul, than a work of old theology?… There must be something wrong if the most important human business is also the least exciting.”

He goes on: “Those early friends of mine bought the book when they thought that it solved the mystery of Berkeley Square, but dropped it like hot bricks when they found that it professed only to solve the mystery of existence. But if those people had really believed for a moment that it did solve the mystery of existence they would not have dropped it like hot bricks. They would have walked over hot bricks for ten miles to find it.” This book, he says, “may stand as a type of all the new theological literature. What is wrong with it is not that it professes to state the paradox of God, but that it professes to state the paradox of God as a truism.

You may or may not be able to reveal the divine secret; but at least you cannot let it leak out. If ever it comes, it will be unmistakable, it will kill or cure. Judaism, with its dark sublimity, said that if a man saw God he would die. Christianity conjectures that (by an even more catastrophic fatality) if he sees God he will live for ever. But whatever happens will be something decisive and indubitable. A man after seeing God may die; but at least he will not be slightly unwell, and then have to take a little medicine and then have to call in a doctor.”

Connected with this insight that true theology cannot be boring is the realization that lies at the heart of Chesterton’s thought about Christianity, as it does at the heart of Balthasar’s (and that of his teacher Henri de Lubac), that there is something in Christianity that can never age, that can never become old; something that is always brand new. “A century or two hence Spiritualism may be a tradition and Socialism may be a tradition and Christian Science may be a tradition. But Catholicism will not be a tradition. It will still be a nuisance and a new and dangerous thing.”

Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger speaks of the centrality of conversion to theology for this very reason. Conversion is the acceptance of the “new beginning in thought” — as it is also a new beginning in life — brought about by an encounter with the Incarnate Word. Both faith and philosophy are equally essential to theology, but they can be integrated only through the process of personal conversion. For conversion involves transformation and deepening; it is “the indispensable means for penetrating into the truth of one’s own being”. This is why, he says, “in every age the path to faith can take its bearings by converts; it explains why they in particular can help us to recognize the reason for the hope that is in us (cf. 1 Pet. 3:15) and to bear witness to it.” For Ratzinger, this is the real purpose and meaning of theology: to recognize our reason for hope, and to witness to that hope in the life of the mind.

It would not, then, on the basis of this formulation, be foolish to argue that theology in our day should actually take its bearings from a great convert like Chesterton — and perhaps particularly from those books, such as Orthodoxy (1908) and his later book The Catholic Church and Conversion (1926), in which he describes and accounts for his own conversion to Christianity and to Catholicism, or The Everlasting Man (1925) in which he gazes upon the event of the Incarnation with a convert’s freshness of vision and wondering astonishment. Chesterton himself in the second of the books just mentioned calls conversion “the mark of the Faith”: that is, as in some way belonging to the essence of the Faith and not merely a necessary point of entry to it which we gradually leave behind us.

This means, also, that there can be no very clear distinction between theology and what has in recent centuries been called apologetics — for apologetics is also the art of bearing witness to “the hope that is in us”. Apologetics is generally aimed at those who are yet to be converted, while theology is for those who may be presumed to have the faith already; but in Tremendous Trifles Chesterton observes that converts are always in need of conversion: “I believe in preaching to the converted, for I have generally found that the converted do not understand their own religion.”. (Once again, this blurring of the sharp distinction between theology and apologetics is something we notice in the work of de Lubac and Balthasar.

A theology that aims to communicate the attractiveness, the excitement, the glory of Christianity cannot help but be a form of evangelization. Conversion becomes a permanent possibility for the Christian thanks to the Sacrament of Penance. Indeed, the claim of the Church to forgive sins was one of the main things that attracted Chesterton to Catholicism. As he says, the most hardened and hoary sinner may emerge from the confessional as innocent as though born one minute ago. This is the miracle of the old becoming young, of the sun rising in the evening of the world:

And sudden as laughter the rivulets run

And sudden for ever as summer lightning

The light is bright on the world begun.

– The Towers of Time

It is amazement at this supernatural morning that we catch in Chesterton’s voice when he writes of the faith; and when we hear it we are reminded of the Apostles who stood blinking long ago in the same dawn, which is the dawn of theology.

The Sword of Surprise

A little book called Paradox in Chesterton by Hugh Kenner is extremely pertinent to our theme. A “paradox” is, of course, a statement that at first sight appears absurd, either because it seems to contradict itself or because it contradicts accepted opinion. Examples can be found in every paragraph of Chesterton’s writing; it is the most noticeable, and to many the most irritating, feature of his style.

Kenner shows how his use of this device is not, as it may appear, a weakness, but flows from the “direct intuition of being”, a metaphysical vision into reality as such. It is, in fact, closely connected to the fact that Chesterton writes as a convert, and from the depths of his experience of the encounter with God. It reflects the very process of his thought: its continual reconversion or revitalization in the meeting with the real. (And in his case, as Noel O’Donoghue points out, thought is never far from imagination; it depends for its effect on images and vivid metaphors.)

To defend Chesterton’s use of paradox is not to commend him as a literary stylist. Believing that “the Edwardian decay of art and thought is traceable” to the neglect of paradox and the denial of its importance, Kenner nevertheless admits that as an artist Chesterton had other, more serious faults. “Chesterton the writer scarcely left a page that is not (as he would have cheerfully admitted) in some way botched or disfigured: nor is the deficiency that vitiates the bulk of his poetry and fiction merely technical.” But it is not his merits as an artist that concern us here.

The point is about paradox, and it is this: that Chesterton did not so much make paradoxes as saw them. He was able to discover them because they exist in the world all around us. Most of the time we fail to notice them because we are content to think in cliches and truisms, or in metaphors that have rusted solid. (Kenner calls this “mental inertia”.) And this is precisely why Chesterton’s statements so often appear absurd when we first encounter them. Absurd, or hilarious. The clue, for me, is provided in the Introduction to The Defendant, particularly at the beginning and at the end of the following passage:

Religion has had to provide that longest and strangest telescope — the telescope through which we could see the star upon which we dwelt. For the mind and eyes of the average man this world is as lost as Eden and as sunken as Atlantis. There runs a strange law through the length of human history — that men are continually tending to undervalue their environment, to undervalue their happiness, to undervalue themselves. The great sin of mankind, the sin typified by the fall of Adam, is the tendency, not towards pride, but towards this weird and horrible humility.

This is the great fall, the fall by which the fish forgets the sea, the ox forgets the meadow, the clerk forgets the city, every man forgets his environment and, in the fullest and most literal sense, forgets himself. This is the real fall of Adam, and it is a spiritual fall. It is a strange thing that many truly spiritual men, such as General Gordon, have actually spent some hours in speculating upon the precise location of the garden of Eden. Most probably we are in Eden still. It is only our eyes that have changed.

The passage both provides several examples of Chestertonian paradox, and helps to explain why they are theologically important. It is a paradox, seemingly in flat contradiction to received wisdom, that the primary sin of man is not pride but humility. It is a paradox that the Fall was an undervaluing not of God but of ourselves, and even that we are capable of undervaluing our own happiness. But above all it is a paradox that we live on a star that has to be discovered.

The last of these is the fundamental paradox that underlies almost everything that Chesterton tried to do and which he expands, not only through each of the various chapters of The Defendant but through a dozen stories in which he portrayed a character who goes away from home in search of adventure or treasure and succeeds — eventually, after many vicissitudes — only by returning to the place he left, this time with eyes wide open. He begins Orthodoxy by saying,

“I have often had a fancy for writing a romance about an English yachtsman who slightly miscalculated his course and discovered England under the impression that it was a new island in the South Seas. I find, however, that I am either too busy or too lazy to write this fine work, so I may as well give it away for the purposes of philosophical illustration.”

In fact, of course, he was too busy to write it because he was writing that very story in a thousand other guises, and not least in his religious essays and apologetics. His purpose was always to “renew our acquaintance with things” (as Kenner says), including religious doctrines, by making us see them as though for the first time; by opening our eyes and showing us Eden.

It was not that Chesterton evaded the effects of the Fall. The reason that he was able to regain and retain his childhood innocence of vision was — he would have said — the fact of the Incarnation and Redemption. He was able to live, as it were, in Eden because the world has been washed clean and made new again by the birth and death within it of the Son of God. It is therefore as a Christian and not a pagan that he points to the beauties of an environment and of a life that sin has obscured. He perceives, as Julian of Norwich did, the whole world held in the hand of God like a hazelnut, issuing forth in every moment from the love of God like a fountain. “He was accustomed,” as Kenner says, “to looking at grass and seeing God”; to seeing “not lamp-posts but limited beings participating in All Being” (p. 44). And this gift was connected with a fundamental “habit of thought” that can be called thankfulness. “I would maintain,” he wrote (in A Short History of England, although it might have been anywhere), “that thanks are the highest form of thought; and that gratitude is happiness doubled by wonder.”

He himself calls this a “faith in receptiveness” and “respect for things outside oneself”. When once we can see things for the first time, we become grateful for the gift of life itself as one might be grateful for a surprise party or a win on the lottery (a win so big that it enables us to have not just a round-the-world cruise with our closest friends, but life, friends and the world itself).

We did not deserve to be born: we could do nothing to bring it about. But to state this in philosophical terms is one thing. To express it, as Chesterton does, in paradox and poetry, is quite another. Take his Introduction to the Book of Job.

“God will make Job see a startling universe if He can only do it by making Job see an idiotic universe. To startle man God becomes for an instant a blasphemer; one might almost say that God becomes for an instant an atheist. He unrolls before Job a long panorama of created things, the horse, the eagle, the raven, the wild ass, the peacock, the ostrich, the crocodile. He so describes each of them that it sounds like a monster walking in the sun. The whole is a sort of psalm or rhapsody of the sense of wonder. The maker of all things is astonished at the things He has Himself made.”

Or take the passage in Orthodoxy, where he compares the world to the things Robinson Crusoe pulls out of the sea. “The trees and the planets seemed like things saved from the wreck: and when I saw the Matterhorn I was glad that it had been overlooked in the confusion.”

“That there are two sexes and one sun, was like the fact that there were two guns and one axe. It was poignantly urgent that none should be lost; but somehow, it was rather fun that none could be added.” In such ways does Chesterton convey the fact that the world itself is something to be thankful for, which rather lays upon us the obligation to consider whether there is someone to thank for it.

As I have suggested, paradox as a technique is well suited to a writer who is a perpetual convert. Not only does it help us look at things “as though for the first time”, but it is a way of bringing out something paradoxical in the nature of reality, and particularly in the nature of Christianity. One might even argue that only someone with a talent for seeing paradox can do theology. Kenner makes much of the fact that for St Thomas Aquinas being is intrinsically analogical.

The idea of analogy is the idea of “likeness at the core of difference”, or of one thing mirroring another within a greater (or even infinite) “unlikeness”. God and man are not, for example, “good” in the same sense of the word “good”, but there is a relationship of likeness that we call analogy between the goodness of God and the goodness of man. Often the best way of communicating a sense of that likeness in the difference is by means of paradox. At the heart of the Christian mystery, we are in Chesterton country. Christmas, the feast of the Incarnation, provides Chesterton with his favourite paradox:

A mass of legend and literature, which increases and which will never end, has repeated and rung the changes on that single paradox; that the hands that had made the sun and stars were too small to reach the huge heads of the cattle. Upon this paradox, we might almost say upon this jest, all the literature of our faith is founded…. Any agnostic or atheist whose childhood has ever known a real Christmas has ever afterwards, whether he likes it or not, an association in his mind between two ideas that most of mankind must regard as remote from each other: the idea of a baby and the idea of an unknown strength that sustains the stars.

With the Incarnation, “the whole universe had been turned inside out”. In Hinduism, too, there is a story that Krishna’s mother looked inside her child’s mouth and was startled to see there the starry heavens and infinite worlds. Chesterton would have liked the story, but he would have seen in it a prophecy or intimation of what only became true with Jesus and Mary. Other religions (notably Zen) may employ the technique of paradox, but none is founded on a living paradox as apparently absurd as to be complete “foolishness” to the Greeks and a “stumbling block” to Jesus’ own people (1 Cor. 1:18-25, 2). The wonder of Christmas is that the Lord of heaven and earth came forth from a human womb, and entered into a human life. In The Queen of Seven Swords, Chesterton’s poem called a “Little Litany” is a commentary on the titles attributed to the Blessed Virgin Mary in the Litany of Loreto. It includes the lines:

Star of his morning; that unfallen star

In the strange starry overturn of space

When earth and sky changed places for an hour

And heaven looked upwards in a human face.

Or risen from play at your pale raiment’s hem

God, grown adventurous from all time’s repose,

Of your tall body climbed the ivory tower

And kissed upon your mouth the mystic rose.

A Christmas creche is a never-ending source of delight for Chesterton for, “it is the paradox of that group in the cave, that while our emotions about it are of childish simplicity, our thoughts about it can branch with a never-ending complexity. And we can never reach the end even of our own ideas about the child who was a father and the mother who was a child”. He does not forget, either, the note of drama and peril, the presence of the Enemy at that feast of Christmas, the danger of death and the massacre of the innocents that it would provoke.

He finds in that tableau with the shepherds and the kings the whole mystery of the life and even the death of Christ. What he calls here “the mightiest of the mysteries of the cave” is the paradox “that henceforth the highest thing can only work from below”. Heaven is now under the earth; royalty “can only return to its own by a sort of rebellion”. This was implicit in Mary’s Magnificat, that God “casts the mighty from their thrones and raises the lowly”; it will be a theme running right through the teaching of Christ, from the Sermon on the Mount to the Washing of the Feet. And it will be carried to its conclusion in the death of Christ and his descent into hell.

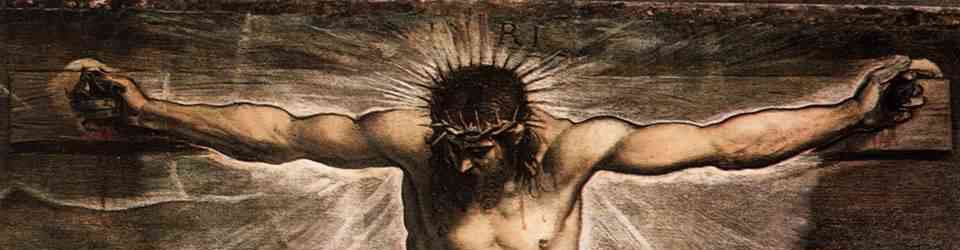

Compared to his remarks on Christmas, Chesterton’s comments on Easter — the Passion and the Resurrection — occupy little space. It was almost as though he shied away from applying the full power of his imagination to a mystery that tragic and glorious, and could not bring himself to “play” with it in his mind and with his pen as he played with the idea of Christmas. The reason is not that he took less interest in the Cross than the Crib or took it less seriously, but that it lends itself less easily to his kind of commentary.

Of course, in The Everlasting Man he does not avoid the topic altogether. He begins by contrasting Christ with all other philosophers, prophets and founders of religions. Jesus came not to teach, but to die. He came not so much to fulfil the philosophies as to fulfil the mythologies. The death of Socrates could only be what Chesterton called the end of the philosophers’ picnic, or at best another lesson to his disciples, the lesson on how to die. But “Death was the Bride of Christ as Poverty was the bride of St Francis”. Unlike the Buddha, “The primary thing that He was going to do was to die”. There is nothing morbid about this, as Chesterton might have remarked; Jesus had to die because his object was to overcome Death, and Death could only be conquered in its own domain and at the height of its strength.

At this point in his chapter on “The Strangest Story in the World”, in a passage of remarkable eloquence, Chesterton sets forth his reasons for not writing at length about the passion of Christ. “The grinding power of the plain words of the Gospel story is like the power of mill-stones; and those who can read them simply enough will feel as if rocks had been rolled upon them.” “It is more within my powers,” he says, to point out that, just as “kings and philosophers and the popular element had been symbolically present at his birth, so they were more practically concerned in his death”.

By this he means that they were either involved in killing him, or involved in being unable to save him. They represent “the great historical truth of the time; that the world could not save itself.” “Rome and Jerusalem and Athens and everything else were going down like a sea turned into a slow cataract.” At this precise moment in history, the Cross was the turning point. And at the deepest point of the Passion Chesterton senses the mystery at its very heart, of which the sign is the great cry of abandonment: My God, my God, why have you abandoned me? He writes:

“There were solitudes beyond where none shall follow. There were secrets in the inmost and invisible part of that drama that have no symbol in speech; or in any severance of a man from men. Nor is it easy for any words less stark and single-minded than those of the naked narrative even to hint at the horror of exaltation that lifted itself above the hill. Endless expositions have not come to the end of it, or even to the beginning…. and for one annihilating instant an abyss that is not for our thoughts had opened even in the unity of the absolute; and God had been forsaken of God.”

There are no deeper resources for reflection in theology than these. It is noticeable that in the last words I have quoted Chesterton again presents a parallel to Balthasar. Chesterton’s sensitivity to the mystery of Christ was so great that only this greatest of modern theologians can do justice to the depths of his insight. Balthasar makes much of the fact that an “abyss” had opened “even in the unity of the absolute”, which yawned wide enough to encompass all the lostness of the world. His “theology of Holy Saturday” is a remarkable (and still controversial) development of that insight, guided in part by the experiences of the mystic Adrienne von Speyr.

Even Chesterton’s remark, quoted earlier, that God can be “astonished at the things He has Himself made” finds an echo in Balthasar’s Theo-Drama. Notice, finally, that in Ch. VIII of Orthodoxy Chesterton even touches on that controversial theme in Balthasar, the possibility of universal salvation. “To hope for all souls is imperative,” he writes; “and it is quite tenable that their salvation is inevitable. It is tenable, but it is not specially favourable to activity or progress.

Our fighting and creative society ought rather to insist on the danger of everybody, on the fact that every man is hanging by a thread or clinging to a precipice. To say that all will be well anyhow is a comprehensible remark: but it cannot be called the blast of a trumpet.” So, he concludes, “Christian morals have always said to the man, not that he would lose his soul, but that he must take care that he didn’t.”

To pursue this thought further would take us astray, but at least we are beginning to see something of what Chesterton meant: there are secrets that theology has not begun to touch in two thousand years. Once again, we realize that the Christian religion is not old; it has barely begun. And however far it travels in its continually renewed beginning, the job and the delight of the theologian will be to circle around the same two points, points that define the centre of a circle whose perimeter is the cosmos itself: the birth of God and the death of God, Christmas and Easter.

The “Amateur” Theologian

Chesterton’s use of paradox (and even his fondness for puns) places him in the company of the Fathers of the Church and the great Christian poets, such as Donne, Traherne, Crashaw, Blake, John of the Cross, Hopkins and Eliot. I do not claim that he was as great a poet as any of these, because such comparisons would be pointless and even ridiculous. No more do I wish to claim that he was as great a theologian as Irenaeus or Augustine. But just as he was indisputably a poet, if only because he wrote and published some fine poetry.

I do now wish to claim that he was — given our earlier definition which liberates the word somewhat from its modern academic context — a “theologian”; that is to say, an explorer of Revelation, endowed with a generous measure of intellectual grace. One sign of this indwelling grace is pointed out by Kafka: “He is so happy, one might almost think he had discovered God.” More than the natural fruit of a happy childhood, and unlike mere placid contentment or self-satisfaction, this overflowing joy seemed to come from an unknown depth and communicate itself to those around him.

It was manifested, too, in his gift for friendship: even those who disagreed with him most violently (such as George Bernard Shaw) admitted they loved him. Chesterton was not a “man of the world” but a man of the Kingdom, a man who lived in the light of that Paradise which awaits us on the other side of the Cross. He was a man of letters; but he was more than that. He was one who put the letters together in a way that makes sense. He was a man of the Word.

A word is a sign, and has a meaning; it expresses something. By saying one thing, it denies another. It is a light that shines in the darkness: when it is spoken the darkness is separated from it. Chesterton gloried in the definiteness of words; he positively basked in the capacity of light to cast (and to cast out) shadows. He loved the dogmatic quality of Christianity, its ability to divide right from wrong and true from false.

Against the “liberal” theologians and so-called “free-thinkers” he asserted that it is the dogmas of Christianity — the dogma of free will, for example — that set us free, and the refusal to believe them that closes “all the doors of the cosmic prison on us with a clang of eternal iron.” He loved words and dogmas not for their own sake, but for the sake of the one Truth, the one Word, the one Reality that shines at the heart of all words and gives them their strength as it gives them their direction.

That one Truth, spoken in the language of the body and the language of history and incarnate in the man Jesus, speaks itself in many other fragmentary ways. In fact everything (in its deepest reality) is a word, or a letter in a word, that refers to him. We see this intensively in Holy Scripture: in the pattern of types and antitypes, of prophecies and fulfilments, that the Church Fathers loved to dwell upon. For them as for Chesterton, the symbolism of Scripture merely crowned a symbolic character present in reality itself.

This comes out in many places, but particularly in William Blake (1910), where Chesterton speaks of Blake’s “realism”: a “rooted spirituality which is the only enduring sanity of mankind”. In this Blakean realism, the things we see about us are real because they are symbols; they are real to the extent they contain within them that which makes them what they are — the monkeyhood of the monkey, the lambness of the lamb, even the motorishness of the motor car. Similarly at the human level, “The personal is not a mere figure for the impersonal; rather the impersonal is a clumsy term for something more personal than common personality. God is not a symbol of goodness. Goodness is a symbol of God.”

Thus God for Blake “was not more and more vague and diaphanous as one came near to Him. God was more and more solid as one came near. When one was far off one might fancy Him to be impersonal. When one came into personal relation one knew that He was a person.” God is the most concrete of all realities; not the most abstract. And so, despite the inconsistencies and even heresies he notes in Blake (which he sees as a betrayal of the poetry), Chesterton enlists him on the side of orthodox Christianity. “Realist” mysticism suits Christianity down to the ground: all it needs to become sacramental is for God to become incarnate at its very centre.

Chesterton writes that the truest religion is the most “materialistic”. An incarnational or sacramental quality runs right through Christianity like a kind of watermark (at least in its Catholic and Orthodox traditions). Only through the incarnation of God does the material substance of the world become more than the illusion it must be for all other religions and philosophies — because, of course, for them it is doomed to come to an end. That is how Chesterton saw things, and it means that he has seized on the one point that really makes Christianity unique and unassimilable.

“Paganism was the largest thing in the world and Christianity was larger; and everything else has been comparatively small.” Firm in his grasp of this essential point, he was able to trace — especially in Orthodoxy, Saint Francis of Assisi, Saint Thomas Aquinas and The Everlasting Man — the central line of Christian thought through the centuries. Each of these books, it will be observed, are presented as historical (or autobiographical) rather than theological. But precisely because history has become theology in Christianity, they are at the same time theological works.

The sacramental principle is the “golden key” to Chesterton’s vision of reality. Two years before his death, Chesterton wrote in G.K.’s Weekly, “Before the Boer War had introduced me to politics, or worse still to politicians, I had some vague and groping ideas of my own about a general view or vision of existence…. I had it in the beginning; and I am more and more coming back to it in the end…. my original and almost mystical conviction of the miracle of all existence and the essential excitement of all experience.” In the light of this conviction, “the most common thing becomes a cosmic and mystical thing. I did not want so much to alter the place and use of things as to weight them with a new dimension; to deepen them by going down to the potential nothing; to lift them to infinity by measuring from zero.”

This “almost mystical conviction” lies behind the gratitude Chesterton felt for the very gift of existence — that gift whose permanence and value is finally guaranteed only by the Incarnation of God and the Resurrection of the flesh. The “most logical form” expressing that gratitude is in the act of giving “thanks to a Creator”, and in that act “the commonest things, as much as the most complex, …leap up like fountains of praise”. One thinks of the Canticle of Daniel, in which the Church herself gives voice to these “fountains of praise” leaping up from the clouds of the sky, the showers and the rain, the darkness and the light, the mountains and hills, the birds, beasts and children of men.

One thinks, too, of the Mass; for the supreme liturgical act of Christians is “Eucharist”, thanksgiving, the “sacrifice of praise” in which the Son of God offers himself to the Father in the power of the Holy Spirit through a human priest, the only perfect expression of the love of man for God and God for man.

Chesterton’s spirituality, his whole psychology as a Christian, was “eucharistic” — that is to say, a joy in existence overflowing into thanks. It was, by the same token, Trinitarian, for it is in the Trinity that all thanks begin and end. The Son receives everything from the Father and his gratitude is boundless. He gives to the Father in return all that he has received. That exchange of love includes the creation, which the Father entrusts to the Son and the Son redeems with his blood, handing it back to the Father in the act of giving up his Spirit on the Cross.

At the centre of the Incarnation, which culminates in the Passion, is the act of eucharist, the sacrifice accomplished only by way of total abandonment. It is this eucharistic character in his life and his writing which marks Chesterton as a “theologian” in the deepest sense. He was a theologian whose thought unfolded the supreme and simple truth that the creation springs from nowhere but the love of the triune God. He was an amateur theologian, for an “amateur” is one who loves, and the love of God is the best qualification for theology. He is a theologian, finally, who leads us by the way of paradox, from darkness at noon and the mystery of the shedding of blood, into an undying dawn as “sudden as laughter”.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Stratford Caldecott “Was G.K. Chesterton a Theologian?” The Chesterton Review, November 1999.